You can enjoy this blog post by listening the podcast episode, or you can read it here, whichever is more convenient for you.

YouTube | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | iVoox | Google Podcasts | Amazon Music

In coaching, we have not started talking about iatrogenics because it is what we have been calling “technique training” for a long time. This concept is referred to the harm caused to a patient as a result of medical treatment. According to Nassim Taleb, iatrogenics extends to any complex system, such as financial, political or social. It is the damage and side effects we can cause intervening a complex system when it would be better not to touch it: in United States there is more people dying from prescription of opioids than from car accidents. Trying to eliminate a small pain, there is an intervention —the over-prescription of painkillers— that ends up creating a huge damage.

I know what I am talking about, I have seen it with my own eyes and I have caused it with my own actions. Although science reminds us that the less instructions and technical feedback provided, the more success… as a padel and basketball coach I have been trying to increase the effectiveness doing the opposite. I have spent a lot of time judging “technique” of my players as “good” or “bad” based on a “perfect technique” that only existed in my head. I have corrected game movements that were successful, simply because they deviated from the universal pattern of “perfect technique” I had in my mind. A textbook case of iatrogenics —and perfect example of Dunning-Kruger effect also.

As haters of uncertainty that humans are, I guess I could not accept that someone could succeed with a movement, a way of doing… that was not what I thought it was “good” or “correct”. During many training sessions, instead of being a good professional and putting the player first by helping her find her best version, I believed that the player was someone who was at my disposal: I made her imitate that “perfect technique” I thought it was correct, forcing her to be as I thought was ideal. Instead of helping the player, I was only thinking, selfishly, for myself. A coach is someone that helps people to improve at a sport; I wasn’t coaching, I was making the complex reality fit my erroneous and outdated beliefs so, at the end, I could think: “What a good coach I am!” I have provided specific corrections to players about how to place the arm, leg or wrist, how to hit the ball... which have not meant any improvement, but quite the opposite: it caused “paralysis by analysis” making the player feel unable to make a decision due to overthinking. Instead of owning up to my iatrogenics, I blamed the poor frustrated player to do not do things “in the right way”. Actually, I was just blaming her for not doing things “in my own way” or “in the way I wanted”.

Looking back, I am not proud at all of that selfishness present in me and I think all this was caused by the fucking belief that there is one single “perfect technique”, “tactic” or “physical skills” that every player must achieve. Nowadays, I am tired of creating unnecessary harm and it is clear to me that people and players come first. Then we go, the coaches, as companions. The following phrase always comes to mind...

“Welcome to all those coaches who understand that this consists of rolling up our sleeves and leaving everything for the children and not by making the children roll up their sleeves and make them leave everything for us.”

I have broken with the reductionist tendency that for years has affected most training methods: we have been fragmenting components of complex systems —such as sport—, we have addressed them separately with simplistic methods harming more than helping, not contemplating at all the need and adverse effects of our interventions. Isolating the “technique” from the other competitive components —variability, uncertainty, decision-making...— we have developed the belief that there is a “perfect technique” whatever competitive context in which it is applied.

I resign myself to think that performance is made up of different components such as “technique”, “tactics”, “physics”, “psychology”, that each has a closed ideal form that must be analytically achieved to reach “perfect performance”. I resign myself to practice them separately because in the game we find them all together, interacting.

Pirelli already warned us that Carl Lewis’ perfect skills can be useless if he runs in heels. Stephen Curry's shooting form will not be functional if the physical condition, the perception of the game, the control of emotions... do not accompany. It is useless having a sharp ax if I do not even know where to start cutting the tree.

It is a story of a farmer and his horse: One day his horse ran away and his neighbor came over and said, to commiserate, “I am so sorry about your horse.” And the farmer said “who knows what is good or bad?” The neighbor was confused because this was clearly terrible. The horse was the most valuable thing the farmer owned. But the horse returned the next day and he brought with him 12 feral horses. The neighbor came back over to celebrate, “congratulations on your great fortune!” And the farmer replied again “who knows what is good or bad?” The next day the farmer’s son was taming one of the wild horses and he was thrown and broke his leg. The neighbor came back over, “I am so sorry about your son.” The farmer repeated: “who knows what is good or bad?” Sure enough, the next day the army came through their village and was conscripting able-bodied young men to go and fight in war, but the son was spared because of his broken leg and… “Who knows what is good or bad?”

—Chinese parable

A specific “technique” or movement, or any “tactic” or team behavior pattern does not exist outside of the context it is applied in. Who dictates whether a technique —from an individual or a team behavior— is “good” or “bad” is not the coach and his beliefs, but the functionality of it in the moment of the game it is performed. “Who knows what is good or bad?” Look at the situation and the movement usefulness to answer it.

I have decided to start with the “whole” and adopt a vision more consistent with the complexity of the sport. The main goal in any sport is to win. Does the rules of your sport condition the way or form you must use to do this? If it does, as is the case in gymnastics, it makes sense to train the “technique” and maybe even talk about the “perfect” one since it will provide us with more points and probabilities of winning. But... in the case of football, the rules tell us which “technique” we must use to win? Will a “beautiful” goal be worth more than one? Will an “ugly” and “lucky” one be penalized? No more questions, sir. If “technique execution” is not mentioned in the rules of the game... does the concept really exist or is it a myth that coaches have created? Focus on the game, its result and help the player or team figure out their best way to achieve it.

“Whatever is superfluous becomes ugly over time.”

—Alvar Aalto

What rewards more in a tennis match? Execute the “technique” perfectly as detailed in those books, manuals and tutorials or have more winners and fewer unforced errors than the opponent? The scoring system does not provide any incentive to perform the “socially accepted technique” that your coach loves so much, but to know how to put the ball in the specific place, at the specific time and at a specific speed in order to win the point or make the opponent miss. When the player is clear about what she has to achieve, the “how” emerges involuntarily and spontaneously according to the characteristics of the moment and of who is executing. But we, wrongly, prefer to make them try to control the uncontrollable, to consciously move body limbs that must flow. It’s not my opinion, they are Bernstein’s facts. When coaching we give instructions on how to place the elbow, how to finish the shot... and the player focuses more on what to do without paying attention to the relevant competitive information that has to guide her behaviour and will help her succeed: perceive where the opponent is, where can attack her, which space is free, how to win time... All these competitive factors that condition and make the “technique” of that moment emerge.

If the training is based on repeating and memorizing the “perfect technique”, will it be transferable to the competition if the player has not studied the “technique” books hours before? In training, in closed, unreal situations... what will guide her behavior? The game or the memorization of the coach’s instructions? In the game, when she has to flow and has no time to think, will she be able to pay attention to the relevant stimuli of the game? Or will she fail because is not able to memorize the instructions of “technique” books on which the training is based? Will she know how to perceive the relevant match information that she must use to guide her actions if in the training sessions she has been just memorizing and moving, not perceiving and acting? What will happen if we have limited her to having the role of executor and we have forgotten that the player must also, necessarily, be a perceiver? It is not necessary to order the “how” based on shouts and orders, the best instructions we can give are, silently, to introduce competitive elements such as the rival movements and shots, uncertainty, variability... which will cause the player, at every moment she is in, to learn to use that specific “technique” of that moment in order to succeed.

“Beauty if it is not functional is not beauty.”

—Jorge Wagensberg

But... if we break with “technique training”, what are we going to talk about? I propose to talk about functionality: the quality of being suited to serve a purpose well; practicality. It focuses on what it matters: the purpose, the intention, the “why”; to win or achieve a goal and it takes into account all the factors that are involved in competition. If a pattern or movement used by a tennis player in a specific situation of the match allows her to achieve her purpose on a specific situation (such as winning the point, move the opponent towards one direction to win the next ball or just putting the ball in because she is under pressure), it is functional. If the movement pattern or its intention —no matter how “beautiful” or similar to the one in the “technique” books is— does not serve to achieve the goal, it is not functional. The attention does not have to be focused on the imitation of fictitious standard models, but rather on understanding the singularity of the player and if she achieves the goal or solves the specific problem of the specific moment of the game. If the player suceeds in ugly or unconventional ways, great! If you worry about her adaptation in the long term, challenge the functionality. Propose the player a more difficult competitive challenge and look what emerges. Remember, though, to judge the funcionality of the solution she proposes, not if it is more or less similar with your desired “technique”.

Since we are not robots, we cannot be understood outside the context in which we find ourselves. To study how a Chinese car works, I can take out the part I want to study —or the whole car—, take it to a Finnish or American mechanic and nothing will change. Humans work differently: the context does not change a car but it does change us; we will not behave the same in China as in Finland or a Mediterranean place. The “technique” emerges from the person-environment relationship. The “technique” appears from the characteristics of the player and the situation in which she finds herself. A soccer player, at a specific moment, has a specific purpose, such as scoring a goal, and relates to the environment surrounding her in order to achieve it. A short, left-footed player with little confidence, in the right part of the area... in a 1v1 in front of the goalkeeper will use a different movement than a tall, right-footed striker with a lot of confidence in her abilities that fins herself in the same spot. The characteristics of the player and the specific competitive moment make the “technique” appear. The fact that in this world no two players and moments are the same means that there is no single “technique” for everyone. What will decide whether the “technique” of the left-footed player and the right-footed player will be “good” or “bad”? It is the functionality in that context —the specific player and environment—, if it serves to achieve its purpose: to score a goal. A movement is correct when it perfectly fits a motor problem just as a key easily opens a lock. ”Do not care if it is “cute” or “ugly”.

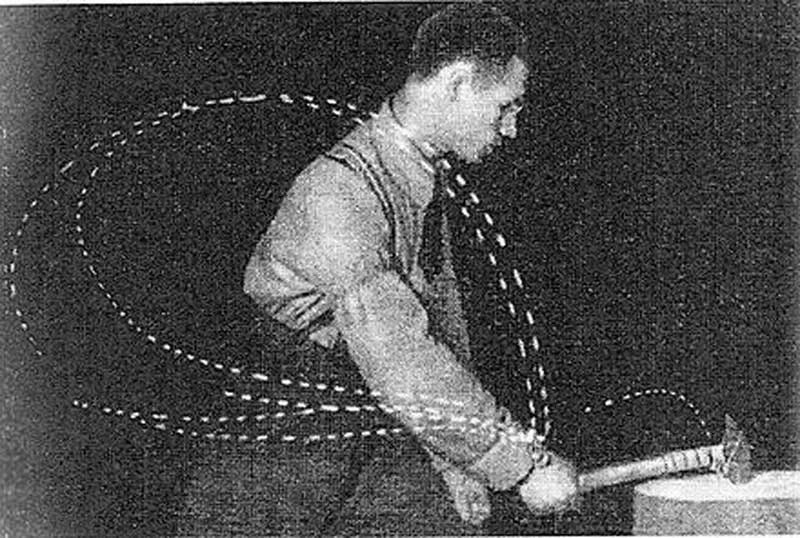

In the club of “technique training” destroyers, our Bible was drafted by Nikolai Bernstein. In his study analyzing blacksmiths hitting a hammer, he showed that the best ones were the ones who had variability in their “techniques”. The performance key was a variable “technique” to be able to adapt functionally to the changing conditions of every moment, of the environment. If in the school of blacksmiths, the teacher tried to make each person hit in the same way... would we be facing a clear case of iatrogenics in the blacksmith industry? This happened in tennis. The serve was worked on by separating it into phases (toss, hit, follow-through...) and until the former was not performed perfectly, it was not worked the next phase. When the player went to the real game, she found it impossible to perform the same movement every time, to throw the ball in the same way. The key lay in the ability to adapt her movements to the differences in each serve —the variability in the “toss” moment, influenced by the score, fatigue, emotions...— to be successful. The belief in repeating a “perfect technique” to succeed is iatrogenics, it does not help. Give your players tools to deal with uncertain situations, to adapt and encourage them to change, they will thank you. Having functionality means having different tools to win in different ways, not always using the same tool in the same way.

Here —in case that was not enough— I would like to shout to the four winds my unpopular opinion: “technique” is not the cause, but the consequence. It is not about repeating “techniques”, it consists of never stopping to solve problems. On the way to achieving functionality, “technique” appears and not the other way around. What causes a player to perform functionally is that she effectively interacts with her environment and, as a consequence of this, “technique” appears. Movements are solutions of competitive problems: a consequence. For a basketball player who is going for a basket with a defender on the side, the cause is to read the game situation and adapt to it to make a basket, the consequence is the “technique” used to score it. Once she perceives the game situation and is aware of her personal possibilities —a basketball player and her defender can be tall, short, right-handed, left-handed... and can dominate some skills more than others—, she acts by making the lay-up more suitable for that situation: it may be a normal one, a floater, a single step, a change of direction, etc.

Now I understand why Natàlia Balagué told me “we have to stop treating people like they are stupid”. The excess of instructions, control, orders... in order to help, probably causes the opposite: harm, iatrogenics. My players —and I am convinced that yours too— are smart enough to find their solutions, they do not need constant instructions from a prescriber. Trust them a little, please. The problem arises when I make them dependent on me and spend the whole training telling them what to do. It is normal that later, when they are alone in the competition, they do not feel able to find their answers. It is not player’s fault that I am not able to live with uncertainty; to not accept that not everything is “white” or “black”, but that there are many “greys”; of my need to intervene to justify the salary and keep my mind calm; of giving orders to calm my conscience even if they are not necessary and generate avoidable harm instead of remaining silent respecting the time that change processes need.

“A training session is just the expression of the coach and what he thinks his role is.”

I think that every coach practices with abstract glasses that condition the way in which she perceives her players, the team, the competition and the sport. Personally, I think there is still some trace left... but I am trying not to put on the “technique” glasses again and use the functionality ones. As a coach, changing my glasses, pursuing functional behaviours without worrying about the “how” or the “technique”, has changed my perception of everything. I see myself more as a designer of game situations and problems than as a prescriber of game solutions, because players are capable of finding their own. I am someone who modulates the challenge posed by the game so that the team explores and exploits possibilities for action.

The “technique” ones made me look excessively at my mental models, what I had planned in my notebook, what I think is “good” and “bad”... while I missed what happened in the game. With the functionality glasses I feel that I know less, that I lose knowledge... but that make me pay more attention to the moment, to help the player and the team find their best way to win. I do not feel like the boss, I feel like another component of the team. The drills are not anymore isolated, without opposition or uncertainty and based on instructions… but the opposite. The competitive situations, the game problems I raise work much better than yelling and instructions and I remain as an active part in case help is needed. Situations in which we find most of the factors experienced in the game such as decision-making, perception, variability… that include “technique”, “tactics”, “physics”… training at the same time without need of fragmenting these mentioned concepts.

The players and their intelligence, first. Then, in case they need me, I will be ready to help them in the way that I think is most convenient for the team.

Martí Cañellas | Fosbury Flop

Fosbury Flop is for the people, by the people. If it brings you value and you want to support the project, you can help to make it possible recommending it to a friend or upgrading your subscription.