You can enjoy this blog post by listening the podcast episode, or you can read it here, whichever is more convenient for you.

YouTube | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | iVoox | Google Podcasts | Amazon Music

Two posts came out of the shame that was caused to me by devoting myself to teaching and not knowing how one learns. This is the second post in the series on learning and teaching which I wouldn’t have been able to write without the help of Albert Batalla.

I would recommend you to start —if you haven’t read it already— with the first post. You can find it by clicking on the following link:

If you have already read the first, here the second begins. I think it will be very difficult, but I wish you could enjoy it as much as I did.

Coach, teacher... if you have thought about it and, in order for your players to learn and play better, you have no choice but to intervene, remember that learning is not making movements. Learning is solving problems. Means to achieve it, there are some to get bored. I would group them in two major trends, in two major paths to promote learning, to teach. Imagine —I say imagine because it is a false dichotomy— a fork, where you have to choose which path to take and there is a sign with an arrow to the right and one to the left, which says: reproducing solutions (copy-paste) or adaptation. In other words, I could also say: “Obedient soldiers” or players with initiative? The road of adaptation leads to situations that the players must solve functionally. You, coach, don’t stand aside; you, as part of the team, have to help them. The road of reproducing is what the coach —and his “monkey” mind— decides on “perfect” “technical”, “tactical”, game… models that he must teach —or, rather, indoctrinate, force to do...— to the players.

At first, I believed that reproducing models, solutions... was not learning. I thought: if I’m driving and to get to the destination I need to look at Waze continuously, I haven’t learned anything. I believed that learning was being behind the wheel, awake, and attentive to relevant information from the environment —the road— to make the best decisions that would bring me closer to the goal.

Everything changed when I realized that in both ways I could satisfy a need, solve a problem, achieve a goal. Knowing how to go places by looking at the GPS is like competing according to the coach’s instructions. Of course you can win! Can you solve problems by reproducing or copying? Of course you can! You will have learned... yes. But the day your cell phone battery dies or your coach gets kicked out, you’ll be lost!

Reproducing or copying, is it good or bad? Is it better or worse? It depends on your answer to the question: “Is this the learning I want the people I influence to experience?” I don’t want that. I want to know how to drive looking at the road, not the mobile phone; I want to win by paying attention to the game, not to the coach’s shouts. We can reach our destination and win matches by copying or adapting. We can learn from both ways. The side effects, however, will not be the same. It is true that reproducing can facilitate adaptation... but it can also leave negative consequences. As in padel or tennis: training with the bucket doesn’t mean being a mediocre coach, it depends on the criteria behind it. If you think of learning by reproducing as the solution to everything, I don’t know if we’re doing well: if you’re looking to reproduce without over-constraining… maybe yes.

If you behave having memorized all the steps to achieve “success” consciously, you can learn. You will have achieved a learning —from my point of view— crap. Quality learning appears when you are able to achieve this “success” —in the car, in your sport, in life…— by driving alone and without depending on third parties.

What marks the quality of the learning that we promote as coaches? In my opinion —not information— whether what he learns will lead him down the path of autonomy or dependence. After that, will they need you more or less to troubleshoot? That’s why I love physiotherapists —who do it well— and curse the fucking pharmaceuticals. Reproducing models of others or that the coach tells you are correct generates dependency. To behave, you need a 3rd person to tell you what to do. Fortunately, copying or reproducing is not the indispensable means of learning. Being able to adapt —to perk up— in any situation gives you autonomy.

“You will teach them to fly, but they will not fly your flight. You will teach them to dream, but they will not dream your dream. You will teach them to live, but they will not live your life. Nevertheless, in every flight, in every life, in every dream the print of the way you taught them will remain.”

―Mother Teresa

I hope I could explain it as well as Mother Teresa. You can teach them to fly in many ways, but the medium you use will make them fly or dream what you want… or empower them to fly theirs and live their own dreams. Teaching, by nature, is not a purely altruistic or selfish act, it is not empowering or indoctrinating; it is you, as a master, and your actions that will decide what it is and means.

If over time, the frequency with which you go to the psychologist increases... maybe he is doing something wrong. Wouldn’t the goal be for you to be able to live without it? Autonomy is the ability to adapt to different environments. Reproducing is much poorer than adapting and makes you more dependent than autonomous. Copying is not bad, we all copy in the things we don’t master. Even, sometimes also with the ones we know. I don’t know if you can get very far just by copying what others are doing. So is reproducing bad and adapting good? I would say that, in general terms, yes, but the truth is that the only thing that can evaluate them is the answer, exclusively personal, to the question: “What kind of learning do I want the people I influence to experience?”

Don’t think that when you find yourself at the fork of reproducing or adaptation, the two paths you can take have the same value, they are equal. Not everything is worth it, I think. One is paved cooperatively by professionals and scientists and the other by very good professionals, some “monkeys” and the help of many myths that have been protected from scrutiny and analysis. Each path has more or less truth, is more or less effective, is more harmful than the other, is more selfish than altruistic... both paths aren’t the same! But I’m not going to make those moral judgments, because I’ve already made enough of them. The path of reproducing and the path of adaptation are not two state-of-the-art highways that take you to the same place, at the same speed and with the same safety. Rather, one is an innovative highway and the other a conventional highway of the last century.

Does reproducing or copying involve learning? No. Does adapting to the needs and problems of the environment involve learning? Yes. To reproduce means to make a move, but it does not necessarily mean to solve problems. In fact, Albert Batalla explained that he learned to shoot by imitating the culturally “correct” shooting form. With your permission, dear Albert: I don’t think you learned how to make a basket, I think you learned how to make the movement needed to pass the subject. You didn’t necessarily solve the problem of making more baskets —you didn’t learn to shoot; you passed the practical exam— you learned to pass the subject.

If I memorize the steps of the route by car at home looking at the computer but on the road I don’t know where to turn and I don’t know how to link them to the reality I’m in, I haven’t learned... I will have memorized a sequence that is of no use to me. If the player —or Albert— does not find a connection between the movement he makes and the problems he encounters in the game, he will be a good mover-maker who will not have learned to be a better basketball player. He will not be able to fix game problems. If the player knows how to adapt to the problems of the competition and achieve the goals, he will have learned... whatever the move is —if it is allowed by the rules. Another thing is that it is not the movement that we, the coaches, like; that it does not achieve success with the model we have in mind, with the movement that we have culturally accepted. But he will certainly have learned.

Nicolai Bernstein said that we don’t learn to move, we learn to solve problems. Movement is the consequence of solving the problem. Movement is not learning; movement is a sign of learning. Moving is just a tool to solve problems and satisfy needs. You don’t learn a movement, you learn to solve a problem. For this reason, the movement that is applied is contextual. Repeating a stereotypical solution out of context is not learning if the player doesn’t find any relation to a problem they have to solve.

Coach, focus on the game: what goals, what problems, what needs... does it raise? Forget about the movements you have in mind and that you think are the good or right ones. Be little formal and very functional: What is the problem you need to solve? What the hell do you want the player to achieve with that technical gesture (not what movement do you want them to do)? At most, be like Barcelona’s Design: interested in form but respectful with function.

If the aesthetics, the form, of the movement are not contemplated in the regulation, any training proposal based on it is poorly focused. If it is not, forget the form of the movement and obsess over the function it must achieve, the need it must satisfy.

There are no basketball shooters who make lots of baskets but have a bad shooting form. A player who makes lots of baskets is an infallible shooter. Another thing is that you, coach, don’t like the form. I’m sorry, but basketball only cares about function. The game doesn’t care at all about the form. I learned this from basketball shooters and Àlex Terés: as in most sports, in basketball it was thought that to “learn” how to shoot you had to get the mechanics right —form. The truth was that you could do mechanics well and not learn a shit: culturally accepted mechanics did not imply causality with improved shooting, with being a better shooter. To learn how to shoot, the key to the shot lies in the trajectory of the ball —function— not the player’s body —form. Of all the great shooters, no two shot the same way, but in all of them the behavior of the ball was the same. Reproducing the form perfectly does not involve learning; satisfy the function regularly —whatever the form— yes. If your priority as a coach is form, you have all the numbers to be a learning obstacle. If you’re obsessed with the function, it’s likely they’ll learn because of you, not despite your intervention.

“Not every day is the same,

but there are many like this one...”—Ferran Adrià

Sport is the same for everyone. We people are very similar... but we are not the same! But both evolve. Heraclitus said: “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he is not the same man. There is nothing permanent except change.” A solution to a problem can be more or less standardized, the answer it gives can be common. It’s never the same, that’s why. The athlete must be ready to change, to adapt, the day he has to run the 200m and has a micro-injury. The team must know how to solve the problems that the opponent creates when it presents a different defense. “Never change” can only be wished by those who dislike you.

Coach, if you want to know how to intervene and promote learning —not disrupt it— buy a book, look for a scientific article. You can’t base everything on personal experience. If we would read a little bit... If the foundations of your practices are based on your personal experience, let me tell you that their quality will be dubious.

Cognitive biases trick our brains. These affect how we perceive, interpret and remember. “We see things as we are, not as they are”, said Jiddu Krishnamurti. “We see what we know, not what we have in front of our eyes”, said Eulàlia Bosch. The simplistic heuristic “Because someone did this and they learned —or won— doing this is good” disappoints. Prudence! “I have done this and they have learned.” Find out what they learned before!

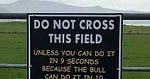

The eye that looks and the brain that reasons do so with ideology and with a desire to see and find things they want. In the bowels of the process there is an invisible network that is difficult to decipher. “We are dealing in a magic realm. Nobody knows why or how it works.” That you see what’s happening doesn’t mean you know why what you’re seeing is happening. Don’t think —neither the good nor the bad— that things have turned out a certain way because of what you have done. It is very difficult to know what everyone gets from what you propose. Maybe it happened despite what you did. “If we put together the 20 most mediocre coaches in a league, one will win.” That the champion of the 1954-1955 season had played that way and won means nothing. See also the graveyard: how many tried and lost?

We must be extraordinarily insolent, out of the utmost respect, with the status quo protectors, with what is already known —for a long time— that we are doing wrong. Do not defend your arguments to me by shouting or saying that you are more. You don’t evolve by confirming what you believe —by changing answers— you evolve by trying to falsify it —by changing questions. Personal experience, quite contaminated, must be a help, it cannot be the compass. Never forget to supplement it with the information that science gives you. And don’t forget to question it either: it’s not the perfect method! But, for now, it’s the best we have.

“Statistics is that science that says that if I eat two chickens and you none... we have eaten one chicken each.” All learning outcomes are statistics. It will never tell you what to do exactly, it will tell you what is most likely to happen when we do according to what. “When people have been given a lot of feedback, this has happened.” There are no methods based on scientific evidence, but informed by it. This is not my opinion.

If you are so stupid that you have to be told, exactly, step by step, what to do... science will let you down. Because the scientific method serves as a guide, not a closed recipe. Do you want your players to learn thanks to or despite your intervention? Science has been telling us for decades that we continue with many practices that make no sense to continue perpetuating. If we would read a little bit...

We learn in social settings. The brain is not a computer, we work differently from machines. We know how to adapt, we don’t need to be programmed. I have already talked about the obsession with the formal and the forgetfulness of functionality. If anyone finds any evidence of the effectiveness of repeating for repeating, out of context, without opposition... let me know. The motor control system understands abstract images better than words: the player must be clear about what to achieve, and not so much what movement to make. The most relevant is the adaptation to the dynamic behavior of a third party (rival, teammate or object), no the “technique” of the textbooks. Focus on the game, not on your own body: technical instructions are a detrimental means of promoting learning. You have to be aware of the problem to be solved, of the goal to be achieved: the muscles, unconsciously and involuntarily, do the rest. The amount of feedback given by the coach is inversely proportional to the benefits it provides to the learner. The more the training resembles the competition, the more benefits. Respect the essence of the game: integrated training works much better than fragmented one. If the learner can do it independently, let him do it and step aside as a coach. Naturalize —accept, live with and learn from— the mistake, but never foment it. The most significant learning happens outside of awareness: don’t make everything go through the conscious and voluntary control of movement. Our concern must be to generate potential learning situations, not to explain the “theory” of what they have to learn. Don’t make learning too easy to satisfy your mind; you will be cheating the player. Order fools us in the short term and is counterproductive in the long term: practice in random environments to retain the skills learned much better. Motivate without discouraging. Don’t generate incorrect expectations (either up or down). Train for the players, not for you; your task is from the sidline outward, not inward.

And how can it be that with so much knowledge, so much experience we still don’t know the best way to teach? “What is the secret?” Everyone wonders... I don’t know... But... May your illusion never leave you, may your passion always accompany you.

The answer to the questions I posed weeks ago appeared in the form of a question mark. I just got doubts, I just got new questions. I know what revolution Jorge Wagensberg was referring to when you change the question. What a mental earthquake. I started looking for answers to: “Why do we learn? How? What’s going on in there?” I finished it, revolutionized and feeling a great responsibility. Since one cannot choose not to learn, I had to change the question: “In what direction do I want the people I influence to evolve? What kind of learning do I want them to experience?”

In this post I have linked the words and let loose some opinion. But I didn’t write it alone. The ideas, the knowledge... have been put forward by professionals who, like John Cotton, realized that those who dare to teach should never stop learning. Thinkers who, like Natàlia Balagué or Bertrand Russell, are brave enough to put question marks on certainties that have been taken for granted for a long time. Teachers who, like Albert Batalla, whenever they teach, teach at the same time to doubt about what they teach.

Those of us who impact the lives of others have the most beautiful job in the world. Fortunately or unfortunately, coaches, masters, teachers... we have great power. We must live up to this great responsibility. The guidance hypothesis describes it perfectly: the coach’s opinion prevails over the player’s results. Even if the player does well, if the coach tells him something different... the coach’s opinion weighs more than the result in the game. If you don’t train well, coach, you’re just annoying, you’ll cause harm. Therefore, the teacher should never stop being a learner. Because if one is no longer a student, one loses the right to call oneself a teacher. Jorge Luís Borges said he was more of a reader than a writer. Toni Segarra says that he is more of a lover of advertising than a publicist.

Hopefully, one day, I can become more of a researcher than a coach, more of a learner than a teacher.

Martí Cañellas | Fosbury Flop

Fosbury Flop is for the people, by the people. If it brings you value and you want to support the project, you can help to make it possible recommending it to a friend or upgrading your subscription.