Dick Fosbury was not an athlete but rather an innovative murderer. With a mattress as his weapon and in a completely spontaneous manner, he killed the straddle technique and its monopoly. Fosbury Flop was the name of that innovative murder technique.

Around the 60s, high jumpers competed using the straddle technique —Valeriy Brumel was its main insignia. This was the best movement pattern that could be performed during those specific years: the athletes were landing after the jump above sand and falling on the arms to protect themselves in the fall was necessary. Brumel and every other athlete who wished to have a long and successful sports career did not even consider landing any other way when jumping over 2 meters in height —Valeriy was already jumping 2.28 meters.

The straddle technique, though, was quite elitist: it required exceptional traits such as a height between 1.85 and 1.95 meters and great physical skills such as mobility, strength and power. The selection process to join the select group of best jumpers was so hard that many fell short before making it. They did not meet the requirements to survive in such a challenging environment.

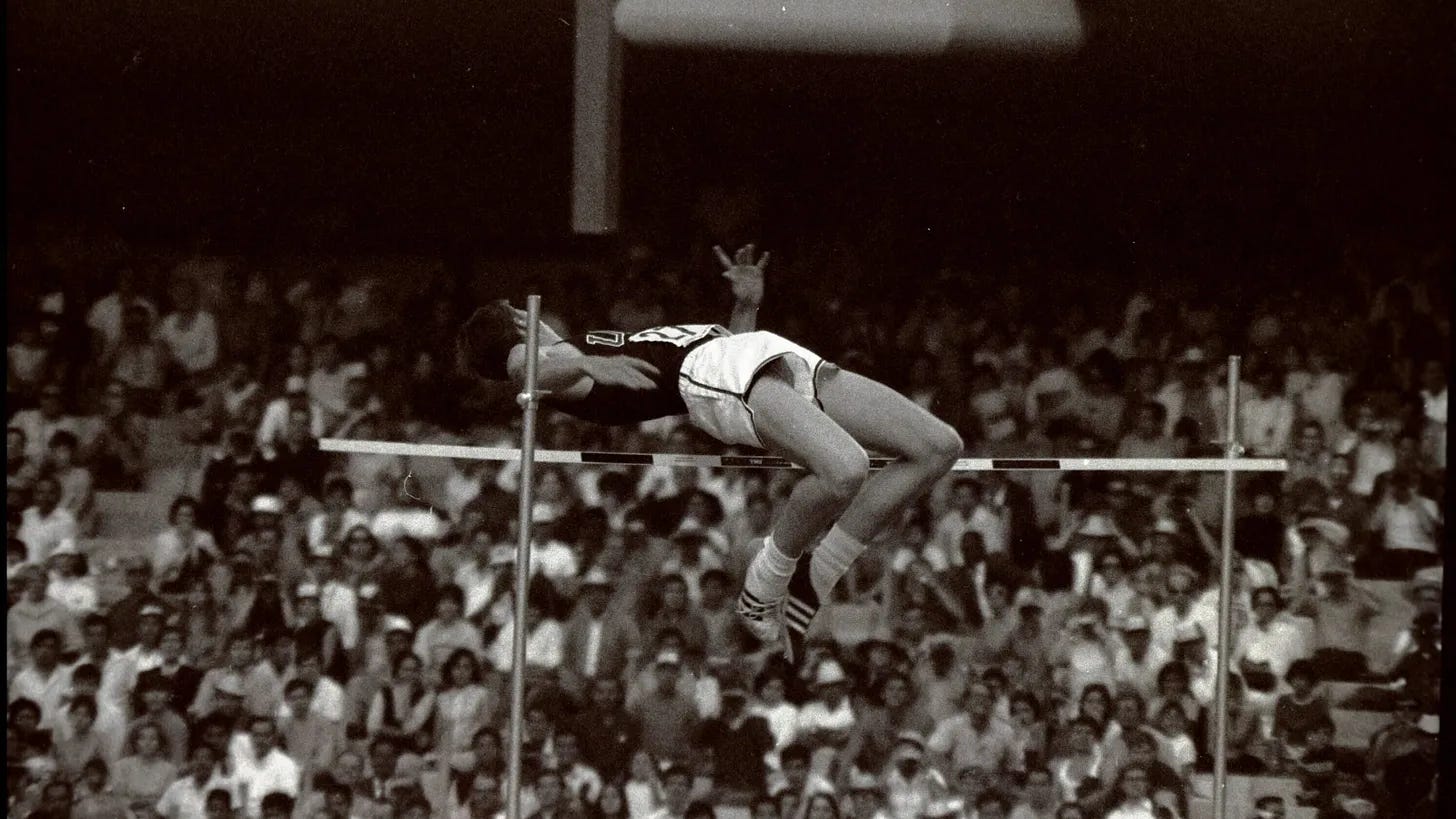

In the midst of Brumel’s reign and the dominance of the straddle technique, a question began to spread among the American athletics tracks: “What is this madman doing jumping on his back?” They talked about him, about Dick Fosbury and his Fosbury Flop. They labeled him as crazy… poor them. Ignorance and mediocrity prevented them from seeing that he was ahead of his time. Dick struggled to jump in the way that the status quo protectors imposed. Many —like US coach Payton Jordan— were disappointed because there was someone who did not fit what their athletic pseudoscience demanded. But Dick followed the true rules: those of the regulation, not the unfounded opinions of mediocre coaches. The spoiler is already known to all of us: the Fosbury Flop —in spite of being heavily questioned— has been globally adopted and has broken all the barriers that aimed to protect those with the selfish monopoly of the straddle technique. At the 1968 Mexico Olympics, he showed the Fosbury Flop to the world and at the 1976 Moscow Olympics, the straddle technique was almost history.

Time has come through, placing Dick and his Fosbury Flop in their rightful place. Because if it had depended on the traditional guardians of aesthetic values, they would still have disqualified him. Time, however, has taken away the credit from another major culprit: the environment. More specifically, it has pushed into indifference Debbie Brill and Bruce Quande —people who could challenge Dick for the title of “murderer of the straddle technique”—, the unconscious spontaneity —that often accompanies greats—, and a mattress. Without them, we would not be able to understand the figure of Dick and his Fosbury Flop.

The behavior of the system cannot be understood independently from its context. We are what emerges from our relationship with the environment. Not all the credit goes to Dick. It is a two-way causation between the organism and the environment. Without his interaction with it —in fact, with two specific environments— the Fosbury Flop would not have emerged.

One of these environments offered him only poor adaptations. The other embraced his personal constraints, providing him with a revolution to a man who only wanted to jump higher… or to avoid failure, nothing else. The difference between the two environments? A mattress.

The environment that only offered him dysfunction had no mattress. It was the current one. High jump attempts landed on sand, slightly hard surfaces, requiring falling face-first to cushion the impact. From the interaction of Dick’s constraints with those of the straddle technique —imposed by his coach Dean Benson— nothing good emerged. He was unable to surpass the 1.50-meter mark. The discomfort caused by his own unorthodox idiosyncrasy made him take “a step back” in high jump. Dick returned to jumping in a traditional way: the scissors style. This approach also allowed him to fall face-first like the straddle technique... and offered him more functionality and comfort.

Dick Fosbury, though, was fortunate to coincide in space and time with a decisive change in the high jump regulations: the landing surface shifted from being hard ground to a mattress. Moreover, his high school was one of the first to install a deep foam mattress for high jump landing. In environments where the mattress was present, the whole story changed.

Over time, we have seen how the mattress became the embodiment of what Lorenz demonstrated: that a flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil can set off a tornado in Texas. The addition of the mattress for high jump was what the freezer meant for the horse-drawn carriage that sold ice bars from house to house in Boston. No one ever had to worry again about landing with their arms. An environmental constraint opened up a new landscape of possibilities and dissolved fears and worries.

Then, during a jump, without being intentionally sought —as often happens in great moments—, the Fosbury Flop emerged. Dick said: “I had that intensity of focus of my mind to succeed. My body simply followed and adapted to the bar, changing its position from sitting up over the bar to lying flat on my back.” That, “the technique developed in competition [the Fosbury Flop] was a reaction to my trying to get over the bar”. Because Dick, “never thought about how to change it”.

The Fosbury Flop was Dick’s —and many other athletes’— natural style in this new environment. He discovered it spontaneously. No prior deliberation or ideation, just functional adaptation to the immediate constraints. His purpose was only to jump higher. It was never his intention to kill the straddle technique or to end its monopoly —that had hindered him so much.

But... if the environment was the same for everyone and all athletes eventually adopted his form, why were not there more contemporaries of Dick who became “murderers”? They did not place the mattress when Dick was jumping and remove it for the rest. The environment was the same for everyone… but no one else shared Dick’s idiosyncrasy. Dick had a unique individuality that could not be expressed by jumping with the straddle technique. He was fortunate that the scissors style was far more motorically similar to the —at that moment, unknown— Fosbury Flop. If he had continued with the straddle technique, perhaps he would not carry the title of “murderer of the straddle technique”. Perhaps Dick would still be searching for his best expression in high jumping. Because it is neither the person nor the environment alone; it is the interaction between the two. The secret lay in the interaction of Dick’s constraints with the constraints of the environments where the mattress was present.

Dick’s story is so powerful because in a very simple —and didactic— way it confronts us with our stupidity: those of us who deal with the behavior of athletes, players, and teams, are used to the opposite. The figure of the coach —and, I think, also that of the teacher— has been a Procrustes blind to the beauty of what surrounded him. Procrustes was that barbarian who mutilated or stretched the limbs of his guests so that they would fit, exactly, in his bed; who eliminated the law of the world: individuality. Rather than dealing with people, we have trained an abstract model of the average person —who did not represent any— that ignored their individuality, their own idiosyncrasy —more or less orthodox.

We have not been coaches. We have been robot coders. Starting from a mental prototype of a standard player —which killed the personal constraints of each athlete— we thought of ourselves as writers of a programming code that would determine the behaviors that would bring him success in the competition. The same code that manifested, causally, equally in each robot. A long complicated list that the “coach” was responsible for optimizing, increasing, perfecting.

We have trained players, teams, assuming that their limits were where their physical limbs ended. We have forgotten that the environment is part of the system —whether we are talking about an athlete or a team. Because the environment is key for everyone: it wakes us up or puts us to sleep, but it always builds us. Ice hockey coach Rick Charlesworth knew this well. As in high jump, the environment causes ice hockey to manifest itself in different ways. Rick knew that it is not the same to practice a sport of short, high-intensity efforts in high latitudes than low latitudes, in humid conditions than dry ones. The location of Atlanta in the 1996 Olympic Games made it difficult for the sport to have its characteristic powerful efforts. The environmental constraints were totally different… and the selection led by Charlesworth was the one who best adapted to it: their preparation consisted of each player being able to play more than one position allowing faster rotations since there were more players who could perform more tasks. Despite the high humidity conditions, they were able to develop the explosive pace of play that characterized them taking the Olympic gold medal. Those who believed that the player and the environment were different, isolated things, I suppose they should have stayed the same, from the sidelines, shouting: “Run harder! Let’s go, team!! Come on!!!”

Thomas Tuchel also sensed something. His mattress was a diamond-shaped field. Unlike others who shout and shout, he no longer needed to tell the right wing to move diagonally into the area. He did not have to force the players to behave in a certain way. He could let the players explore functional behaviors to achieve their purpose in a specific environment. To be more functional like Dick, as a team.

Real Madrid did not water the field playing against Guardiola’s Barça because the environment is part of oneself. They tried to stole a part of themselves, quite necessary, to express their identity. It was fortunate that the Catalans were more autonomous than dependent, more adaptive than fragile, in the search for functionality.

Jordi Coma, my university professor, told me that the best thing that can happen to you in a new job is that you arrive on the first day and have no idea, that you are lost. “You will learn more in the first 10 days than in your entire life, then”, he said. If you want to take the island, you have to burn your boats. The higher you build your barricades, the stronger we become. Revolutions occur in dead ends. When there is fire, one will run faster than in any competition. When one skis downhill, some movements become effortless. Then one may become dumb when there is no real action.

François Jullien explained that a person is neither courageous nor cowardly; but these qualities are found in the environment. The Chinese general seeks success in the situation rather than demanding it from the army under his command. All he needs to do is to put them into a dangerous situation where there is no way out, no chance to escape. There is only one option: to fight as hard as they can to survive. He does not ask his troops to be naturally courageous but forces them to be courageous by placing them in a extremely challenging environment. However, he applies the same knowledge to the enemies: he creates environments that never allow the emergence of the best version of the rival soldiers.

The problems that the separation of person and environment presents us, however, are shown in the field of health. In developed countries, as we build increasingly comfortable environments —and sedentary, and abundant— our relationship with them changes… and what emerges is an increase in cardiovascular diseases, obesity, diabetes… Problems of the first world. Obsessed with everything that is found within the physical limbs of the person, we do not see that the results of most medical trials are due to a greater extent to changes in the environment; or that by improving the biodiversity of urban soils, we improve people’s health.

Given the strength of the environment, we could, wrongly, hold it responsible for everything that happens. The truth, however, is that if we go back in time and put myself in the environments that Messi has lived in… my best skill as a football player would still be sitting on the right side of the bench. “I am I and my circumstance”, said Ortega y Gasset. “I am me and what has emerged from my relationship with the environments I have inhabited”, I would say.

The egg or the hen? The person or the environment? While Carlota and Rafael were dancing a tango, he asked her: “Do you guide me or do I guide you?” Without needing her intervention, Rafael found his own answer: “It could be that you guide me, or that I guide you. My body to yours, and yours to mine.” The person constrains the environment, and the environment constrains the person. I think that is why Rafel Pol suggests that the training unit is the performer-environment system. Because the player’s behavior cannot be understood independently from its context. But it also cannot be understood by assuming the player as a false image of an average model that applies to anyone. The one who can start from an universal model and not pay attention to the context is the programmer, the mechanic; not the coach, the gardener, the doctor, the teacher. Well, that’s it: Dick, acting as a mirror, confronts us with the ignorance that governed the practices of our guild.

That’s why I have become a proud Fosbury Dissident, because he taught me that a coach is the opposite: someone who embraces the player —and all of his specific constraints— so that he can interact functionally with the ever-changing and uncertain constraints of the environment. There is no code to program. There is an environment to interact with, to inhabit. There is an individuality that determines the interaction with the environment and the behavior that results from it. There is no external control that dictates the movements. There is a “power” called self-organization that allows us to adapt, to survive… in challenging environments without orders or instructions, without external control. There is no list of movements that must be performed perfectly in order to be able to engage functionally with the game. There is a complex system capable of exploring the environment to find the meaningful information that allows it to achieve goals, purposes. There is an interaction of specific personal constraints —no two people are alike— with those of the environment —dynamic as life itself. Material constraints of the environment, like a mattress or a friend, but also invisible, as the time one was born or the social norms of your country.

That the challenge of finding functionality in a specific environment can be difficult? The person, the collective, is capable of awakening and refining new capacities, new sensitivities and forms of intelligence... that you, the coach, cannot awaken for them. You can not prevent this awakening. Because there is no coach who can behave for his player, as a programmer can for his robot. There is a professional who should not prevent the adaptation of an intelligent being —but, at the same time, inexperienced— to unknown environments. The coach is not someone who has to pull an ignorant being out of a well. This is a lie that has been sold —with the traditional mechanistic paradigm as a speaker— to ensure that his pocket is not emptied —a bit like what all these personal trainers and individualized training centers are doing.

The perturbation that Dick caused to the system was so great that does not let us stop questioning things. That we cannot promote adaptation to uncertain competitive environments by behaving like robot programmers. That the factory is complicated, mechanistic; reality is complex. That the linear causality of the construction and operation of the car is lost when we leave the factory and discover the non-linearity of the outside world. That if it is not in the computer, one stimulus no longer causes one exact response. That the illusion of control that you have by assembling a robot is lost when you deal with complex systems. That just as each Tesla responds identically to the same programming code, each complex system behaves differently in the face of the same environment. That the environment that is irrelevant to a robot is one of the essential parts of a living being.

So, that: thank you very much, Dick.

Because since I learned the story, when I see failure, lack of efficiency, a desire for functionality… I tell myself that I have to look more closely at the person or the team… and put a mattress. Because, as a leader, I could go with the herd and not stop ordering, shouting, imposing, instructing —which I do not give up completely either. I prefer, however, to be someone who adds mattresses. More of an environment designer than a solutions prescriber. Someone who does not hinder, who facilitates.

Because, for decades, the norm has been to adapt the person to fictitious models that each coach of the day preferred —the coach Dean Benson imposed the straddle technique on Dick... by the way. By distancing the player from what he is and what he feels… how could he do anything meaningful? Everyone ends up adopting a general model that satisfies no one. But to play, train, compete… live, one has to do it as he is: that is when he can bring out his best version… and no one beats him to being himself. Stop trying to be liked, accepted or followed by the herd. It is when one is loyal to oneself that one can do something interesting. It is when the player decides to be himself and not be the homogeneous production line robot that his “coach” wants to turn him into. The best way to succeed, to adapt, to fit environmental constraints is to be true to your own personal constraints.

And thank you, Dick, for pointing out the sun to us… even at night. Because while they shout at us, they repeat, that this is about chasing forms, your pedagogy goes in the opposite direction of the status quo. You show us that what counts is the satisfaction of the function. That is when the form appears. That you have to believe more in what you find than in what you seek. That what many call “technique” —or “tactics”— appears from the functional co-adaptation to the environment. Because the Fosbury Flop emerged thanks to a mattress… and a guy who was not at all comfortable with the status quo, that only wanted to jump more and was brave enough not to betray himself.

Martí Cañellas | Fosbury Flop