You can enjoy this blog post by listening the podcast episode, or you can read it here, whichever is more convenient for you.

YouTube | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | iVoox | Google Podcasts | Amazon Music

In this post, I have put the words and Robert Hristovski the quality. Thank you for your help, Robert.

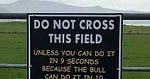

History is changed by those who don’t find balance when and where everyone is stable.

Even if we point to individual beings as being guilty of innovations... we should recognize the part of blame that the context has: it may change everything. The context changes the stability of behaviours, makes them possible or impossible. Context decides whether the behaviour will persist, how much it will last or how quickly it will decay and switch to some other behaviour.

Dick Fosbury is noted as the creator of the Fosbury Flop in high jump. Without a context in which soft landing surfaces began to be incorporated —previously, the landing was on hard surfaces— he would not have been able to explore and find new ways to overcome his discomfort by jumping with ”scissors style” avoiding the standard “straddle technique”. Could it be that the creator was Dick but the culprit was the context in which he was in?

Currently, in padel, Arturo Coello has achieved world N1 following Dick’s example: succeeding in the opposite direction to what many label as “right” or “normal”; finding his stability far from the status quo. Many blame of this the peculiarity of his individual constraints: a height of 1’90m and a discomfort at the back of the court where all his professional colleagues can play comfortably —just like Dick.

They are right; a lot, in fact. But without a context that made Coello feel uncomfortable, unstable... he wouldn’t have had to explore... and find a new way to succeed in padel. He has found himself in a context where most players were stable... but for him, the “normal” way of playing generated instability: he could not have successful performance on a regular basis. Coello had to find the stability —consistent functional performance— in other ways and has ended up reaching the world N1 padel with an unorthodox style.

This has made me formulate an unpopular opinion: Arturo Coello, unintentionally, can be able to end up creating a big tsunami in how padel is played... as Dick Fosbury did with high-jump. But… could it be, in both cases, that the creators have been Coello and Dick but the culprits are technological innovations and the quality of their opponents —so, the context they were in?

Everyone labeled the jumper as a madman, a black sheep. In fact, the coach Payton Jordan said: “Kids imitate champions. If they try to imitate Fosbury, he will wipe out an entire generation of high jumpers because they all will have broken necks.” Time proved Dick right, though.

I don’t know if the same will happen with Arturo Coello. It will be quite difficult for him to achieve the same importance as Fosbury. What I do know is that the padel player has been able to reach N1 of the world by doing two things that no one had ever done before:

Play successfully in the middle area of the court. A space in which coaches often forbade players to be. It is supposed to be a transitional space in which you should not stay. That’s why they call it “no man’s land”.

Coello has “created” and consolidated the “backhand smash” when he is close to the net. It’s a shoot that no one had ever tried before, no one had seen it being trained, no one had posted any tutorials on YouTube.

This makes me wonder if Coello can be the Fosbury of padel. Why?

Although the essence of the game is different, padel is a sibling sport to tennis. It has the peculiarity that the court is a little smaller and is surrounded by glass and fences. This results in players always having a second chance to hit the ball after it has hit the wall as long as it has not taken the second bounce in the floor.

Padel coaches usually separate the zones of the court into three: back part (close to the glass, behind the service line), front part (close to the net) and “no man’s land —transition area— (between front and back). The main idea is to be able to be in the front part most of the time: it’s easier to make points, control the opponents and avoid mistakes. To achieve this, it is necessary to “survive” in the back part of the court until you have a chance to counterattack —usually with a deep lob— and run to the front part. If the lob is not deep enough, the opponents will hit the ball before the bounce and come back to the front part.

The illustration below may help you to understand the “traditional padel logic”:

A very good example of this traditional and common style of play is Federico Chingotto —short player, wearing red. From the back, he is able to resist, survive… as much as necessary until he finds an opportunity to send the rivals back and go to the front zone:

OK. Understood! Now, in the same situation, we change Federico Chingotto for Arturo Coello —the left handed player who wears black:

These are video clips from last season and you don’t need to be an expert to see that... something is wrong. You can see Coello’s partner, Fernando Belasteguín —16 years in a row N1 of the world—, following the “traditional padel logic” —like Chingotto— and looks like he has everything under control. Looks like Belasteguín and Coello are two opposite poles: the former had a stable performance under the “traditional padel logic”; the latter, Coello… didn’t even know where to start.

Following the status quo, Coello is supposed to be in the back part until he can counterattack. But he couldn’t follow this “traditional padel logic” because before he had any choice to counterattack, he had already lost the point, he didn’t survive. His performance was unstable, he couldn’t find solutions, his behaviour wasn’t functional. Arturo Coello failed to have stable successful performance regularly in the back part of the court. He had to explore —forced by the context— other forms, to look for new solutions… in order to have functional performance in the padel court.

The survival of a behaviour —in life and in sport— is dependent on (un)stability. In the back part of the court, the only stable behaviours that Coello had were the ones that caused him mistakes… the opposite of what he needs to succeed. In abscence of stable performance, Coello could be seen anxious to cross the line and approach the net to see if he could find functional behaviors to stabilize in that part of the court.

If you’ve been around for a while, you’ll know what is a complex system. You will call me tiresome if I repeat that we are not machines —complicated systems— but people —complex systems. The behaviour of a complex system —Coello is an example— appears as a result of the different conditions that exist in him and in the environment as his habitat.

Arturo Coello —as every player— consists of many cognition-action components which interact among themselves and also, as a whole, with their environment —teammate, opponents, climate, balls, etc. As we have said: the existance of a behaviour is dependent on its (un)stability in a specific context. The player needs to explore for environments where the strength —or synergy— of the system’s components is stronger than the intensity of the perturbations from that environment.

The high competitive environment where Coello competes perturbs him through the game. The perturbations that Arturo Coello had to face while playing traditional padel were stronger than what emerges from the interaction of the components of his system: they destroyed the interactions of his cognitive-action system, his successful performance.

The more the system —so, the player— is stable, the larger the perturbation is needed to beat him. It is not the case of Coello: as his behaviour was unstable, no big perturbations from the opponent —shoots, moves…— were needed. If the perturbations of rivals were challenging, they would make Coello stronger. Since they were of an unbearable magnitude for him, they kill him. Taleb explained it very well to us with the hydra, the phoenix, and the sword: If a behaviour is perturbed and is not affected, recovers quickly or even grows, it is robust or antifragile and can succeed; if it doesn’t recover or dies, it is fragile. When Coello was placed in the back part of the court was fragile to perturbations. He couldn’t negotiate the shoots played by his rivals. The perturbations were stronger than he could bear. The behaviour, even if we coaches force it, will be destroyed by the context. But this also has benefits and it surely helped him become N1: they forced Coello to explore new ways to achieve his goals.

The back part of the court was —maybe it still is today— a repeller for Arturo Coello. That is, a place where the functional behavior of the player is unstable. As a mountain top is for the water of a river, when Coello is in that place, he tends to leave it spontaneously and converge to the attractor. When it rains, the valleys are attractors of all the water that comes from the sky: areas where they tend to end up fluently. Where is Coello’s attractor? Far away from the back part.

Coello needs to play his own padel, not the traditional padel, the one everyone plays. Maybe he could play it when he was competing at U18 or U16 with players of his age. The perturbations of those rivals did not pose a problem for him to play traditional padel as they do now when he competes against the best players on the planet. He is the same; the context —and its perturbations—, no.

A change of context can make a previous stable state, unstable. Change his opponents, from players of his own age to the best players in the world, and you will see. Coello was faced with the need to find a style in which he could successfully deal with perturbations in the highest category of world padel. It was time for positive feedback: in the midst of an unstable moment, the components of the Coello’s complex system underwent a rearrangement to adapt to the new context.

His cognition-action components found an attractor in “no man’s land”: a place in which coaches forbid you to stay but where his system tends to have stable successful behaviors. In video format it is better understood:

You can see how, as soon as Coello can, he tends fluidly to move towards “no man’s land”. It is a pleasure to see how he can successfully play in an area where, in theory, nobody should be. Thank God that the solution has not been to improve his individual technique with isolated drills repeating the defense execution feeding him balls from the basket to make Coello fit to the textbooks model.

Each player has a characteristic landscape of attractors, repellers and valleys that conditions their path to success. If the player’s landscape leads the water to a certain state, it will cost a lot to go against it. Through training and constraints, we can modify the geography of each player; we can help to create new attractors and repellers that change the stable successful behaviour of the system. But… it’s not us —the coaches— who decide; it’s them —the players— who adapt.

Why don’t Coello —like Fosbury— achieve his goals by following in the footsteps of those who did it before him? Because the behaviour depends on the context the player is. The context —the person in that specific situation— made it impossible. The behaviour is determined by key constraints from Coello and the environment in which he is in.

A constraint is a limitation on the degrees of freedom of the complex system, it guides and influences its options of behaviour. A constraint can be personal or environmental. Both are important in the case of Coello and Fosbury. The different constraints in the context of both did not give any option to follow the tradition. Different personal and environmental constraints made them achieve their purpose in an unorthodox way. Their context was unique: who and how they were and where and when they competed. It also required a unique response, they had to be up to par. Copy-paste wasn’t worth it —or possible.

The height of 190cm is a big personal constraint for Coello. In padel, this big body helps him in the front part but makes him suffer, a lot, in the back. It is so much more difficult to play close to the ground, to bend, to defend the sliced balls from the opponents that hit the glass. Nowadays, it happens more and more due to the high-demanding competition and the exponential level increase in recent years. One has to get better and better at playing close to the carpet. For Chingotto —the short player you saw earlier—, his 170cm height helps him when playing at the back and returning low balls. It’s obvious, isn’t it? So why do we assume that two very different players will play the same padel? Will they follow the same logic? Even if they are in the same environment, there is a gulf of difference in personal constraints —how they are. This influences each player’s path to success when competing. It was the same for Fosbury. His personal constraint was not the height but the personal discomfort jumping with what was “normal” at his time: the “straddle technique”.

Environmental constraints are also largely responsible. Due to exponential growth, technological innovations, changes in the rules... today’s padel is not the same as yesterday. Yesterday’s perturbations have nothing to do with today’s. The player —complex system— must find other foundations to have stable performance. There is also another environmental constraint that has changed from one year to the next: Coello has gone from competing with the veteran Fernando Bestaguín to forming a partner with the young Agustín Tapia. That the latter has a more adaptable physical condition has been key for Coello when it came to feeling confident to move forward. Having a partner who you know is watching your back changes everything.

Dick Fosbury should also build a monument of gratitude to the environmental constraints. Specifically, the incorporation of soft surfaces —and the mattress— to land on. If you can land in a mattress, the worry about falling badly disappears. Dick was able to flow from jumping with “scissors style” to creating, spontaneously, the Fosbury Flop.

We can see the role that trust plays when breaking with what has always been done. In both cases this confidence has been provided —I don’t know to what degree— by the environment. It has been partly to blame for them of not being afraid to jump into the future in a way that no one had done before... and I’m not specifically talking about track and field.

The same dependence on context that has made Fosbury and Coello reinvent themselves is what has prevented their previous colleagues from being innovators.

In padel, previous N1 like Belasteguín, Paquito or Lebrón had no problem being the best following the traditional game logic, they felt comfortable. So... why change? On their way to the top, they encountered no perturbations that destabilized their successful performance. A different personal constraint —Coello’s height— completely changes the context and asks for a new solution. However, the competitive level of the past was not, by a long shot, like the current one. Maybe players of Coello’s stature weren’t as perturbed as he is today and didn’t need to explore different ways to suceed. Could it also be the coaches’ fault? Instead of providing contexts that foster exploration, challenges, variability... have they made his players to adapt to their closed model? Maybe we would have discovered the “Coello style” sooner and it would have gone by another name...

In the high jump, the best jumper was Valeriy Brumel. He felt comfortable with “straddle technique”. Same than before: why change then? He had no need to do things differently. Only problems urge for problem solving and to be creative. However, the rules did not yet contemplate the mattress to land: he had to fall on his face with his arms in front of him to protect himself. Landing from over 2 meters high... you can’t fall on your back. This already causes that in that context, Fosbury Flop could not appear. Nobody asked for a new solution.

That’s why Coello, like Fosbury, did not achieve his goals by following in the footsteps of those who did it before them. While the traditional style of play has been favorable to Chingotto or Belasteguín —just as it was to Valeriy Brumel in high jump—, it has played against Coello —just as it happened to Fosbury. There was a need to break with the status quo and find his own way.

Coello has found stability of the high-level performance in the “no man’s land”, avoiding the low performance caused by the back of the court. This doesn’t mean that this is Coello’s only stable functional behavior. Complex systems, thanks to multistability, can have more than one stable behavior. It usually happens, however, that the system shows preference for a particular one. Sometimes coaches and their love for over-constraining do more harm than good but, luckily, complex systems are goal-directed and adaptable. They have purpose that makes them adapt and evolve to satisfy it. Unlike computers, complex systems can do it alone, spontaneously: nothing and no one organizes them. Fosbury wanted to jump higher. Coello wanted to be N1. This made them self-organize, in their own unique way, to achieve their goals.

The non-linearity of complex systems is also largely to blame for this beautiful story. Changes may not be proportional: the same inputs may have very different effects. The same constraint can greatly affect Coello’s behaviour and not Chingotto’s at all. Small differences between two players can cause very different behaviours: Ale Galán measures 4cm less than Coello and 16 more than Chingotto. Despite being closer to Coello’s stature, he plays more like Chingotto. Galán complex system has found his successful behaviours in this way. We cannot pay attention to the linear stimulus-response relationship because small constraints can largely change behaviour when the system is close to a critical point: where what was stable until then becomes unstable.

Coello’s path to becoming the youngest N1 in the history of padel has taught us that success often has more to do with letting the player express himself fully than molding him to the model that the coach wants. He found an attractor of successful performance in “no man’s land” and changed the game for his opponents. When he stands there, the part of the court behind him disappears making the court smaller for them. Coello will make all the opponents better because he will force them to adapt to this new scenario that he proposes. I hope they thank him. Juanma Lillo said that “the regulations are the best tactics book ever written”. Perhaps we should read less manual textbooks published by “coaches” who think they have the overall picture of how the game should be organized, with players simply needing to comply his instructions. Maybe we should just look more at the rules and the game: these ones tells us to, above all, in padel, pay attention to missing less and getting more winners than the opponent... but it doesn’t delimit the model or the techniques to use to achieve it.

Coello’s second great innovation has been a winner backhand shoot: a black swan. It was assumed that only white swans existed until in 1697 English colonists discovered a black swan in Australia and dismantled all existing scientific theories. Coello with his powerful backhand —and the characteristic style of play mentioned above— has been the black swan of current padel.

Until today, most of backhand volleys were played sliced to the glass or the fence or drop-shot. Then, Coello arrived dressed as an English colonist and executed the backhand kicking the ball out of the court after bouncing in the back glass. I dare not name the shoot, only point to it. As Gabriel García Márquez said: “It was so recent, that many things lacked numbers, and to mention them you had to point to them.” I leave this matter of putting fictitious limits to reality and naming models to the status quo protectors and monekys.

Here you can watch his innovation:

Like the English colonists, he dismantled all the theories that padel is played in a specific and closed way, that everything is made up, that the coach has all the answers and has nothing left to learn.

As in the case of the Fosbury, Coello playing in his style and executing this shoot shows us that to be truly creative is needed the rare confluence of personal, task and environmental constraints. Fosbury’s invention emerged thanks to the confluence of the inclusion of the mattress, his personality trait that caused him discomfort with the status quo and his idiosyncratic preference to jump with “scissors style” instead of “straddle technique”. Behind Coello’s case, there is a perfect alignment of the three types of constraints. His personal characteristics, the constraints of the environment and the demands of the game match perfectly: he created his own style of play in the “no man’s land” and executing shots like the mentioned backhand. Don’t ask Chingotto or Belasteguín, who does not have his power, height or the same dominant hand... to execute the same shoot. In his case, the personal constraints do not align with those of the task and the environment. He, the short player, will find other answers. He will be able to invent different shoots in different situations. If we make him play like Coello —because it’s trendy or because it’s the current “correct” model—, we’re going to fail, we’ll make him fail.

The same with Dick: It teaches us how a rate-limiting constraint may be lifted to trigger exploratory behaviours and, as a result, the invention of a highly novel solution such as the Fosbury Flop. It is not reasonable to pursue —or sell— the same “optimal” learning pathway for all learners. Solutions need to be dependent on the person, time and place. Learning pathways, thus, creation of performance solutions for a given movement task… are individual.

Competing in the Fosbury style, breaking with the status quo and with how padel had always been played, Arturo Coello found his stability. When the geniuses could express themselves as they were, they reached their maximum potential... and changed the sport. Respect the players and the essence of the game. I remember when a status quo protector said of Arturo: “I don’t like Coello because he can’t defend two balls in a row in the back part.” [Typically, the back of the court is assumed to be the defense area.] How can you say he can’t defend two balls in a row if he is the N1? Of course he can! Another thing is that he doesn’t do it the way you like it or that he doesn’t follow the “correct” model you have in your mind. Let your players be who they are, don’t be so selfish to make them be who you would like. The secret is to adapt to reality. Your own one and that of the rivals.

This geniuses weren’t “wrong”, but ahead of his time. Paco Seirul·lo already warned us with a historic sport: “Football is not something completely done, but something to be done.” Well, imagine how much he has left to evolve to padel, a sport that is just starting to take its first steps.

Dick and Arturo, thank you for teaching us that we will never be able to capture padel —or any other sport— and that just because things are one way doesn’t mean they can’t be changed. It has been a great lesson for all of us who, at some point, have thought that we already knew everything, assumed that padel was completely done, that everything was invented or that there was nothing left to learn. May God free us from being orthodox.

Martí Cañellas | Fosbury Flop

Fosbury Flop is for the people, by the people. If it brings you value and you want to support the project, you can help to make it possible recommending it to a friend or upgrading your subscription.