From today, each blog post will have its written version, will be in podcast format and also in video with subtitles. You can enjoy this blog post by listening the podcast episode, or you can read it here, whichever is more convenient for you.

YouTube | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | iVoox | Google Podcasts | Amazon Music

If we were 20 years in the past and you had to take a plane, I would recommend that you first look at the nationality of the flight’s co-pilot. But that isn’t the case, we are in 2023 and we have already learned the lesson. I apply it to our field: If you want to choose a good coaching staff, first analyze the culture in which its members grew up.

South Korea has one of the tightest cultures in the world, characterized by social order and a high degree of respect for authority. Its airline Korean Air had a failure rate 17 times higher than any other. The main culprit of it was the cultural legacy. It was pouring rain and visibility was poor when Korean Air Flight 801 was very close to the ground. Its co-pilot didn’t want to suggest firmly to avoid the landing. The plane suffered a devastating crash.

Korean culture had forged a respectful way of communicating with higher authority that prevented offense or embarrassment. Due to their way of being, it wasn’t very likely to push back against the main pilot. The less experienced the pilot, the safer the flight. It was more likely to question their decisions.

The cultural legacy played against the Korean Air Flight 801, the whole company and its high failure rate. Culture influences success, failure, our personalities… and addressing this impact can change outcomes, as Korean Air knows. Culture influences how an assistant coach will work, how players will behave.

“Who we are cannot be separated from where we’re from—and when we ignore that fact, planes crash.”

—Malcom Gladwell

How I behave depends on my characteristics and the environment in which I find myself. The environment that impacts us so much —in life and on the court— isn’t just family, teammates, opponents, friends, the playing field or the town where you live. The environment also includes everything invisible that we cannot see... or measure.

Culture, for example. Behaviour largely depends on the culture we live, the strictness of its social norms. If a characteristic, condition, variable... affects your behavior it is a constraint. The culture where you grow up and live is a sociocultural constraint.

The ice hockey player Pavel Datsyuk, also known as “Magic Man”, had an unortodox sytle and was the best finding sophisticated solutions skillfully. Why? The fact of having been born in the URSS is largely to blame.

It wasn’t needed any coach to introduce variability in training, teach the value of things, collaborate in his peculiar style of play... because it was done by the society of the USSR. Having been born in a country characterized by shortages of goods and resources, he didn’t enjoy the facilities that the other side of the Atlantic had.

In the city of Iekaterinburg where he was born, the ice rinks were outdoor. If the rink was ready, they would put on their skates and play ice hockey. If they found it covered in snow, they played football in boots. It was much more unstable and slippery and they had to play with that conditions. They didn’t need a coach who emphasized developing balance, giving variability in training, understanding and anticipating the game, making fakes to have success... because it emerged on its own, the culture took care of it. Pavel was forged in uncertain, unpredictable environments where behind every action there had to be an intention in the game, a perception of the situation.

“Behind every kick of the ball there has to be a thought.”

—Dennis Bergkamp

Due to the scarcity of resources, there wasn’t material. You couldn’t buy a new stick, you inherited it when the older ones stopped using them and if you broke it, you ran out of it. Pavel is one of the NFL players who uses less sticks and values the material in a way that is difficult to see in today’s world of abundance.

Who taught him the value of things? The culture in which he grew up. In the United States they could abuse the material as much as they wanted, try to score goals putting the sticks at risk... not in the USSR.

Pavel and the USSR’s hockey style of play had its own identity which was given to them by different sociocultural constraints. Culture gave rise to a more accurate and aesthetic style of shooting, a more technical aesthetic form of hockey. In that context, Pavel found his own solutions and he and the whole country created their own style.

There is a social and cultural context and from that there are different emergent features. Sport is one of them, architecture is another. There are different features but the ideals behind them are the same.

Football is played on many different places and the style of play of each context tells us something about that culture. The Brazilian style of play tells us a lot about a culture that loves samba and capoeira, about a country in which football is practiced in the small spaces that streets provide. The big rugby culture that there is in England, influences how football is played: long balls, tackles and hypermasculinity as main pillars. It isn’t as simple as just a correlation like A equals B but the values, mindset… behind.

In Catalonia there is an egalitarian passion for width which manifests on how the space is created, built and shared. You can observe this passion in the way that Catalan people built Gothic churches and in FC Barcelona style of play.

It isn’t that Catalan people love width just for the sake of it, it comes down to Catalonia’s founding value of equality. This value causes width to be prioritized for common benefit. A long and narrow church perpetuates the injustice of the privileged in front and the poor behind. The Catalan desire for equality changed the way Gothic churches were built... in Catalonia. If the church gained amplitude, it allowed as many people as possible to get in the same room and gather around the altar. There was the need of creating shallow and wider arches, and new special techniques of construction emerged. The Catalan ideals made their Gothic churches as wide as possible. The same ideals made that every able-bodied person in Barcelona lent a hand to build Santa Maria del Mar in only 50 years.

Catalan culture influences the architecture of Gothic churches, its terms of construction. Catalan culture is a sociocultural constraint that also affects how Catalan football clubs play… among many others.

Could it be that we could see the appreciation of width in the style of play of FC Barcelona and the Barça Academy teams? In football, the desire for an egalitarian society manifests itself in this way: The wide positioning of FCB’s players maximizes the space on the field. As the team uses all its width passing the ball, many players are involved in each possession. The Barça museum explains it very well: “Our values underpin and guide our style, our way of thinking, and our game. It is through them that we will achieve the goals we set ourselves.”

The design of the Catalan Gothic churches was underpinned by a desire for a more egalitarian society. FC Barcelona’s style of play emerged from these ideals too.

A task you design for your training will never have the same effect in every context. A task might be the same in Catalonia or in the URSS. The personal and environmental constraints not. At the same time, there will be also other different sociocultural constraints acting above them impacting people’s behaviour.

The social norms of our culture affect how we behave. They have a strictness that isn’t random. A culture is tighter or looser depending on the threats —disease, natural disasters, scarcity, wars...— that it has endured throughout its history. It isn’t black or white —tight or loose— but a long spectrum with many grays.

The more threats, the bigger the need to create order in front of chaos, the tighter the culture develops. There is no room for the herd to deviate but they are more coordinated, organized and have more self-control. On the contrary, they’re more traditional and closed-minded. That is why the extreme right alarms you with so many “threats”. They promote a tight mentality that scares you and only benefits their interests. But we’ll talk about that another time.

Since loose cultures, like Brazil, don’t face so many threats, they haven’t had this need, resulting in more tolerance for those who decide to leave the herd and break with the social order. Cultures that go towards the looser extreme gain creativity, innovation and are more tolerant... but lose in impulsivity and disorder.

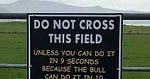

In the same task, facing the same challenge, the Brazilian child doesn’t feel the weight on his shoulders of the cultural obligations as the Japanese one does. As a coach, in Spain you’ll have to bring order and “limit” creativity. To function well, the team will likely need to move away from the loose extreme of the spectrum. The opposite in China: you’ll have to provide confidence so that they feel they can break the “rules” of the team and nothing happens.

In Finland, there was no possession during a basketball match without a set play being called. In Catalonia, when I played as a pointguard, my teammates would yell at me: “Play free!” Coaching padel, I observe a tendency to eliminate gray areas and look for black or white solutions in the north. “Tell me what to do.”

I’m writing this post while watching a padel match between Finland’s N1 pair against a Spanish pair. Every time the Spaniards win a point they shout it out loud. When the point is made by the Finns, they look at each other in silence and clap their hands.

In the morning I went to see the Barça Academy in Helsinki. The director explained to me that the children didn’t celebrate the goals. He had never seen it. They set the rule that if in 5” after scoring, the whole team didn’t celebrate it together, it was a penalty for the opponent. Today they scored and didn’t celebrate the goal but started running looking for their teammates to hug each other jumping and shouting “eh, eh, eh!”.

I find it very curious. Everyone wants to win but every culture has its own way of expressing it.

The culture of the country you grow up and live in is important. Just like the culture you create in the team you lead. Analyze where you are and decide if it should be tighter or looser. See what ideals your players come to you with. Do you need to tighten a loose context or loosen a tight one?

Those who live in capitalist countries that emphasize individuality, competitiveness not cooperation, hierarchy and extrinsic rewards so social comparison... will not behave the same as children who have grown up under collectivist cultures.

Think about what each extreme of the spectrum gives you and what it takes away from you. Ramon Jordana said that a match, like life, is a weighing scale in which you pay on one side and you collect on the other. We all want to collect more than we pay. In order to come out collecting, I would move in a dynamism by tightening when we’re becoming too loose and loosening when we’re becoming too tight. Win it all losing little. Create a tight-flexible or loose-strict culture.

That my leadership isn’t too organized that doesn’t allow anyone to leave the herd or too anarchic where every sheep goes on its own. Master the spectrum to be disciplined creatives, organized innovators. If you are a constant threat, the team will approach the tight extreme. Don’t ask them to innovate if you’re yelling and threatening punishments all day. Don’t ask them to create if your game model doesn’t allow them to break it. Don’t ask them to all go together if there is no order, if they are not moved by the same principles. Control when to create danger that unify and when not to.

Don’t forget the culture: the one you have lived in as a person and the one you make your team live. The values that a person has are influenced by the culture, the historical character and the social order of where she lives. The as used as outdated handshake was the greeting used to show that you had no weapons. The context changes, but what you learned from a young age in a certain place remains even if it is not useful. What you do in Barcelona doesn’t have to be applicable in Stockholm. There is no copy-paste. It influences us as people, mark us as players and we forget the coaches.

Learning is deeply contextual and the result of countless interactions between many people and places.

Skills, learnings, styles of play... have a story.

Martí Cañellas | Fosbury Flop

This post is not mine. I have only limited myself to gathering knowledge that I have found in my life’s path. I invite you to consult the resources that have made it possible. I hope you enjoy them as much as I do:

Rule Makers, Rule Breakers: How Tight and Loose Cultures Wire Our World | Michele Gelfand

Pavel Datsyuk: Learning, Development, and Becoming the “Magic Man” | Mark O’Sullivan, Vladislav A. Bespomoshchnov & Clifford J. Mallett

Social and Cultural Constraints on Football Player Development in Stockholm: Influencing Skill, Learning, and Wellbeing | James Vaughan, Clifford J. Mallett, Paul Potrac, Carl Woods, Mark O’Sullivan & Keith Davids

El Clasico: A Story of Catalan Independence (Part 01) | James Vaughan

El Clasico: Inside Camp Nou (Part 02) | James Vaughan

Outliers: The story of success | Malcom Gladwell

Fosbury Flop podcast and blog is for the people, by the people. It’s free, and it always will be.

You can help to make it possible subscribing for free or recommending it to a friend. If you enjoy Fosbury Flop and it brings you value, you can upgrade your subscription to not miss the extra benefits.