Universal Play Grammar

Words of giants | Ted Kroeten

Today begins the section Words of Giants. People with an authentic point of view come to Fosbury Flop to share their wisdom in blog format. They are the signal in the noise, the treasure of this ocean of content that is the Internet.

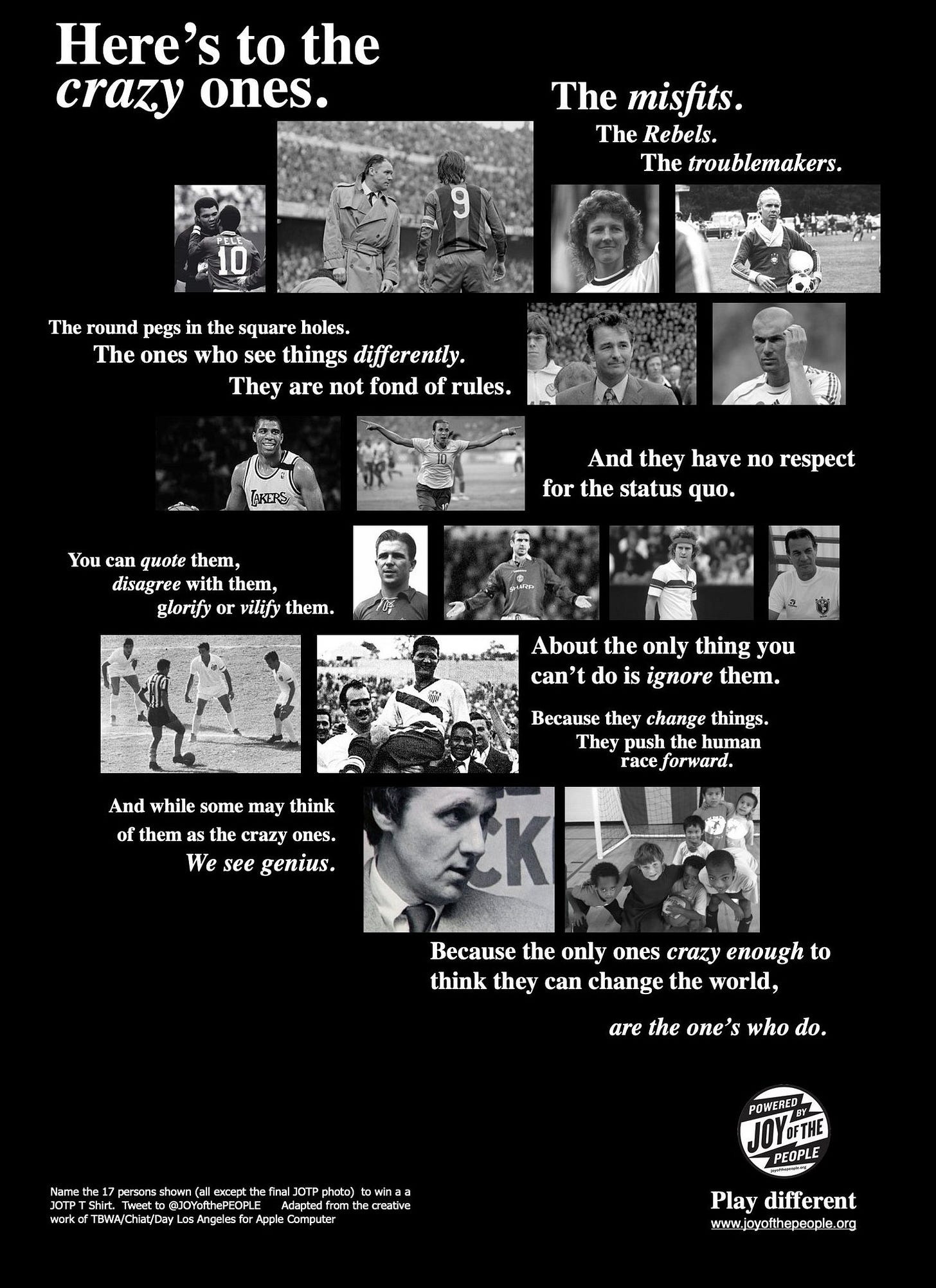

Ted Kroeten is the CEO of Joy of the People, an organization that promotes the idea of soccer free play as a way to build healthy kids and communities. Each year, they provide more than 1,500 hours of safe, monitored free soccer play time at no cost to participants.

I asked Ted: “How would you explain your FreePlay Youth Sport Model to my father?” His answer, below.

Futbolista

It was one of those classic fall days in Saint Paul, the sun-washed through the clear, cool air, the ground dusted with maples leaves crunching under the feat of hustling 10-year-old soccer players in a hurry to jump up on the three-foot cement wall for a water break. The kids fought for positions, their legs dangled halfway down the wall, rapping their cleats against it to create a matching rhythm. The sound brought conspiratorial smiles to their faces. “Look at the noise we can make together.”

The year is 2007 and I am the director of coaching and player development for a large youth soccer club in St. Paul Minnesota. My job is to help kids develop as soccer players. I have been in this role since 2000. Before that, I worked 7 more years, developing skills for the program. Almost every day for 15 years, teaching skills to kids. In the winter, it was futsal and team training in gyms and domes. In the spring, summer, and fall it was camps, team programs, leagues, tournaments, and tryouts. Many of these kids had been with me since the age of four and this was perhaps the best crop of 10-year-olds our club had ever produced. They were taking a water break during their first training session. My good friend, Raffi, was coaching the team.

Sitting on the wall, they were almost eye to eye as Raffi went down the line with a question: “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

“Professional Soccer player”, said the first. “Pro”, said the second. “Professional Soccer Player”, said the third. And down the line, it was the same, until the tenth and last player...

“Futbolista”, he didn’t speak English.

Raffi and I looked at each other. We knew that we had to try something different. It is the job of the 10-year-old to dream, not just for themselves but for all of us. And if a boy or girl dreams of playing in the World Cup, shouldn’t we put together the best education we can think of?

What the kids were asking was how do I get good? We had to ask ourselves what talent is and how do we grow it.

How does someone get good at something? I mean, really good, world-class good? Think of those high performers in sport, business, or any field. We can’t take our eyes off them; we want to be like them, and we ask ourselves: “how do they do that?” and “they make it look easy”.

Think about what we mean with “they make it look easy?” It means that we somehow understand that they are using less effort than those around them, but how they do that? Well, that’s another “story”.

Whether we call it talent, mastery, or expertise, in sports, business, education, and even the 10-year-old child in the backyard with a ball under her arm, everyone is on the big game hunt for this good.

But the reality is talent and skill acquisition is about as understood as string theory, with opinions and methods going in all directions. Despite years of theory, research, practice, numerous best-selling books and more theories, talent and its development remain a mystery. Talent is a gift, talent is mental toughness, talent is the ability to work hard, talent is genetic, talent needs other talent, talent needs adversity, and so on.

And it is not a simple mystery either; it is a mystery hidden in a mystery, within a mystery. It is so complex, so befuddling, that even the expert performers themselves, the ones we want to emulate, cannot tell you how they got good at what they do. They will try, and when they do, they will credit hard work, grit, and the grind of the day-to-day. However retrospective studies of high-level performers find that they consistently overrepresent their hard work hours.

They worked hard, but not as hard as they claim. Why this misrepresentation? Why are the expert performers lying to themselves?

Mysteries can also make great stories, and as you will see as we search for expertise and discover how to learn, improve, and get better, it is all about a good “story”. This lines are the story of our search for talent, and expertise, how to build it, and what we did when those kids spoke to us.

Malmö

Our journey to discovery begins in Malmö, Sweden with a perfect example of expertise, mastery, and the overlooked double secret sauce of expertise. The year is 1999 I was in Malmö, Sweden with a group of U17 boys from my club in St. Paul MN, preparing for the upcoming Dana Cup. Malmö FF, the local professional soccer team, allowed our team to train with their academy kids for a week. On the sidelines, as we watched the Swedish and American boys play, one of the Malmö coaches brought up something he called “the 10,000 hours”. The highest performers, he said, put in more hours than the average performers. Mastery was possible, it’s just that it takes a lot of hours, 10,000 hours to be precise. A psychologist from Florida State had contacted them (he was a Malmö fan) and told them about this concept he was uncovering in his research.

Wait a minute, I thought practice was important, but players were so different in size, shape, and ability, right? Some kids just did things better, and faster. They were born with that, a sort of maximal potential, and the key was to find the right kids and then maximize that talent. What else would it be? Still, this was an interesting theory. The coach went on. They were trying to build in 1000 hours a year for ten years as a club. They were adding practices, trying to get to 20 hours a week. This made some sense, I thought. More practice, to me at the time, meant more improvement, but there was a ceiling, right?

What that Malmö Academy coach was referencing has now become part of the fabric of modern thinking. Based on the research of Florida State’s Dr. K. Anders Ericsson, the “Father of the 10,000 Hour Rule”. He is the lead writer of a now-famous paper, The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance. The idea was to challenge the question of nature versus nature with the conclusion: “Accumulated hours of practice,” they suggested, “were masquerading as innate talent in both music and sports”. In his view, an expert can be judged by his practice history, not his DNA.

“Becoming fitter or more athletic is a function of perfect practice, not genetics.” Dr. Ericcson says: “However, we deny that these differences are immutable, that is, due to innate talent. Only a few exceptions, most notably height, are genetically prescribed. Instead, we argue that the differences between expert performers and normal adults reflect a life-long deliberate effort to improve performance in a specific domain.”

Malmö was one of the first soccer academies in the world to take this approach. As we leaned up against the split rail fence that divided the beautiful training pitches at Malmö FF the coach began scanning the training, he was looking for something.

“That one there”, he said, pointing his finger at a player moving through the finishing drill, ”he has put in his 10,000 hours”. The coach pointed at a tall, skinny player, his shoulder-length hair parted down the middle and held flat with a thick headband. When I watched him, I was struck by how much he did not move like an athlete. When he ran, he wobbled and his knees knocked together. Surely this was wrong.

“Really?” To me there were other players who were faster, smoother, and more “athletic”. “Yes, he is the one. He will one day play for the first team.” I was far from a believer. Just to be sure I would check in with this player down the line, I wrote down his name. “How do you spell his name?” I asked. “Z, L, A…” I read it back: “Zlatan Ibrahimović, that’s right?”

Zlatan would, as predicted, go play for the Malmö first team, and then much more. He later transferred to Ajax in the Netherlands. There, he thrived. He became famous for an amazing solo run vs. NAC Breda. He seemed to dribble half the team, including the goalie for fun just before scoring and it was named goal of the year by Goal Post Magazine.

It was a few years later when I saw that video of Zlatan cutting through the Breda team, making defenders look silly, I said to myself that there might be something to those 10,000 hours. And I was not alone. Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and a slew of other books hit bookstores with what I thought was a refreshing and hopeful notion —that success could be achieved, you just had to be willing to work for it.

Spoiler alert: Zlatan Ibrahimović would turn out to be one of the world’s greatest players to ever play the game of football (soccer). Playing for some of the biggest clubs in the world including Juventus, Manchester United, LA Galaxy, and Internazionale Milano.

Little did I know that the chance encounters with Zlatan and what appeared to be the 10,000 hours to attain mastery would later reveal something very different.

Current models of expertise

We have always looked at skillful performers in wonder. How do they do it? They make it look so easy like even you or I could do it. How did they get there? Was it nature? Were they born that way? Or was it nurture? And if it was something in their upbringing, exactly what was it?

Still, the most common view of talent and expertise is that we are born that way. First, this notion is embedded in how we speak about these people. They are special, geniuses, gifted, born to play (you name the sport). This is also reflected in the systems of selection we have put in place to find these prodigies. While we tell our children and students that “anything is possible”, our systems of selection, audition, and tryouts at young ages give away our real beliefs. There are special kids, and we must find them.

On the nurture side, Ericsson, Gladwell, and others showed us how deliberate practice, a sort of perfect practice on steroids, develops high performers. A story of bootstrapping your way to the top, the “10,000 hours” soon became the banner of educational systems and youth sports —pouring gasoline on the fire of elite development systems (including my large soccer club). After all, if it took 10,000 hours, better get started.

And get started early. The influx of 10,000-hour culture brought serious deliberate practice to younger and younger ages. Dynamo Zagreb begins at U5, Barcelona at U6, Ajax U7. It became a worldwide race to the bottom with more and more pressure on younger and younger kids.

The author David Epstein pushed back with two books in quick succession.

First, in his book The sports gene, he looked at the role of genetics in expertise, providing a cautionary tale to those who thought they could approach any discipline and with enough training, attain mastery. Your genes were important.

Epstein got more specific. or rather unspecific, in his next book, Range. Just as Gladwell leaned on the work of Ericsson and the role of practice, for Outliers, Epstien turned to the work of Canadian researcher Jean Côté and pointed directly at youth sports, this time with Range. This book looked at what Côté termed “sport sampling” as the real route of high performers. As kids, Côté, explained, high performers spent their youth trying many sports, many activities, often in a casual manner, what Côté termed “Deliberate play” a sort of sports activity minus the steroids, a changing variety of games (he coined the variety “sport sampling”) street roller hockey, 3v3 driveway basketball, kid led activities with friends close home. Then later, often later than their near expertise counterparts, they specialized in their chosen sport.

Range and The sports gene both offered an antidote to one of the negative after-effects of the 10,000-hour theory, early specialization. Runaway youth sports and educational systems understood very well that to get to 10,000 hours, you not only had to begin early, you also had to maximize the athlete’s time in the sport throughout the year, and the idea that if you were playing more than one sport, you probably didn’t want it bad enough. But Epstein pushed back hard on early specialization, even its golden boy, Tiger Woods, and openly questioned the benefit of a Wood’s-like pathway. Instead, Epstein offered the Roger Federer model, a success story that Jean Côté himself could have written. Despite having a tennis instructor mom, Federer was a purposeless sports wanderer, trying a bit of everything growing up. “I believe”, he said, “in playing a lot of sports for fun”, said Fed. Both Range and The sports gene encouraged a “fit” strategy. Try things. Find your passion, and see what works and what you enjoy.

Ericsson and Gladwell said to work at it, no, really work at it. Epstein and Côté said you may be born with it, but we are not sure, so try lots of things, and try lots of things to find the sport or activity that “fits”.

Were experts born with it? Or was it a matter of how much and hard they worked at it? Did they specialize? Diversify? It was truly still a mystery.

Cherchez la femme

How to solve this mystery? Film Noir is a cinema term for the dark, expressionistic and suspenseful mysteries especially popular in the 1940’s and 50’s, movies like The Maltese Falcon, The Big Sleep and Double Indemnity dominated the theater-going gestalt, with stock elements: the usual suspects, red herrings, and McGuffins. Our job, like any good detective, is to avoid the dangerous blind alleys and get to the truth. And to help our hero a general hueristic emerged: “Cherchez la femme” (Find the woman).

But this is so much more than a Film Noir movie; this is real life. And in the search for expertise in real life the question good detectives should ask is: “Trouver la pièce” (find the play).

Find the play

In his book on expertise, PEAK: Secrets from the Science of Expertise, Anders Ericsson, the father of Deliberate Practice, advises on how to divine the secrets of exceptional performance: “First, identify expert performers, then look for what separated him from his peers.”

If you look closely at an expert, you will find what separates them. But what actually “separates” expert performers is not the hard work, though it is there too; it is not all the various other activities or sport sampling, but that is likely there as well, what separates expert performers is the time they spent in play.

Experts played. They played as kids do, for fun, with their friends, close to home. And on those loose, enjoyable sandlots, favelas, frozen ponds, and backyard hoops they acquired a language that tilted those uneven fields in their favor.

This play did not build skills, it did not solve problems, or win contests, but it did give them the tools to do those things and more. You see experts as kids became fluent in a sort of play language. This language of play was acquired, not learned or studied, they picked it up the way you or I picked up our native language, unconsciously without much effort.

But we must be sure not to bury the lead: Play is a covert language that experts mobilize more fluently than near experts to complete tasks easier, much easier because they are not doing the work, you are. Play, in an expert’s hands, is a diabolical, mind-controlling device (I told you this was a good story). They score goals, make baskets, and surprise, surprise, get you to help them.

To understand how to build expertise, we must understand the play, what it is, how it functions as a sort of proto-language, how to acquire that language, and how to use it to complete better actions. This will take some searching and problem-solving. So our detective searching for talent will do what any good detective would: return to the scene of the crime.

Zlatan part 1b

As the years went by Zlatan kept rising higher and higher, in 2004 he signed with Juventus, one of the biggest and most important clubs in the world. With his success came news stories, often, they delved into his past and what emerged was not what those Malmö FF coaches conveyed to me five years before. Zlatan had only Joined the Malmö FF youth academy in 1996 at the age of 15. That’s only three years; There was no way he had put in 10,000 hours. If something separated him, It had to be what he was doing before that.

“What Ibrahimović really craved, though, was the recognition and respect he found on the dusty playing fields of the infamous Rosengard projects where he grew up. The area was a mix of Bosnians, Serbs, Somalis, Turks and Poles —immigrants who, like Ibrahimović, were living on the edge of society and never felt they fit in.”

“The soccer pitch became their proving ground, with the raucous games extending long into the night. And just as on the inner-city basketball courts of Brooklyn, Philadelphia and Chicago, winning wasn’t enough. You had to play with style and panache. Tricks and moves were often more important than goals; that was how you got noticed.”

“After receiving a pair of football boots, Ibrahimović began playing football at the age of six. Just outside his mother’s house, on the dusty playing fields of the infamous Rosengard projects, Zlatan taught himself to play. The area was a mix of Bosnians, Serbs, Somalis, Turks and Poles.”

“When we played football in Rosengard, it was all about putting the ball between people’s legs, doing different things,” he adds. “After every trick, people were like ‘oohhh’ ‘eeeyy’. It was all about who had the best trick, the craziest move. I loved it.”

"I loved it."

—Kevin Baxter

As we see, the hours of play that Zlatan put in when he was young look very different than the coach-led deliberate practice filled with feedback prescribed by Ericsson and others. This was just the opposite. This was spontaneous, player-led, and simple. Also, there was no coach to be found. This was a play from the street, free play.

And there was also little mention of multiple sport sampling to see if soccer, as Epstien suggested, “was a good fit”. Certainly when I saw him as a 17 year old football did not seem like a good fit.

But free play, the beloved, mindless, often ignored activities of kids with friends close to home is there. And it is this play that allows us to build talent and attain mastery in almost all fields.

Free play, street play, or unstructured play, has always been revered by coaches, leaders, and administrators, but why? How?

There must be a new understanding of how we learn, acquire, skills, and finally build expertise. Zlatan did not memorize movements, he did not practice specific actions, step-overs, spins, or shots; no, the library of skills required is too vast, and that path is too long.

Universal Play Grammar

Children do not simply copy the play that they see around them. They deduce rules from it, they produce actions that they have never seen before. They do not memorize movements, instead, they use a play grammar that generates an infinite number of new actions.

With these rules they create a “game” language, and here is where it gets interesting. As evolutionary theorist Richard Dawkins says: “We use language to get the muscles of others to work for us.”

How do you convince someone to do something? You tell them a story.

Movements become words, words want to become stories, stories take on meaning which become instructions for action. These “stories” are then employed on others to control them, to get them moving here or there, or maybe just instructions to stand still. The language-built stories convince them to invest resources against their best interest, to even temporarily “switch” teams. Zlatan pulls back his leg to shoot, the defenders then accelerate and slide to block the shot that is coming, but Zlatan does not shoot, he pauses, and lets them slide out of the way, opening a previously closed avenue to goal. A Martian, visiting earth at his very first soccer game, would ask himself as he watched those defenders whose team are they playing for? Because they look like they are playing for Zlatan’s team.

What do we say when we are exposed to a great story? “That story really moved me.”

Pep Guardiola, the great football coach has said: “We move the ball to move the opponent.”

When we play we give off information, intentions, hidden intentions, and so on. On the path to expertise, the goal is to complete the task faster and faster and easier and easier. And what better way to complete a task easier than to use language to convince someone else to do it for you. Like the best con man you ever met, charming, irresistible, exciting. You can not resist. This is the concept of underloading.

Zlatan’s play fluency as a child —developed so thoroughly at the courts of Rosengaard, long before he joined Malmö FF academy at age 16 years old— emerged as a fully formed language he could activate to control the actions of opponents and teammates.

And it does not stop there; Zlatan is also “speaking“ to fans. Growing up with an appreciation of style (“After every trick, people were like ‘ooh’ and ‘ahh’”), Zlatan fully understood the Breda team’s dribbling. Using play grammar to tell those defenders he was about to shoot —when and where the defenders slide to block, ‘but no, that was a trick!’— with this grammar, he constructed meaningful sentences and built a story that was sent to the entire stadium and then the world: “look how easy I can score”. And it was such a good story that if was going to go around the world as fast as possible, that meant, with the advent of YouTube, that the story would find young kids around the world as well as executives from Juventus.

Everyone can learn the language of play, but the vibrancy of play at Rosengaard compared to that of the more sheltered academy allows the “street” kids to learn faster and deeper. Over time, that learning creates a skill gap. This is why Zlatan joining the academy late (age 15) was an advantage, not a hindrance. Playing with his diverse group of friends when he was young, he built this language in a play-supercharger where he grew up.

Over the past 15 years I have been a reluctant part of a unique experiment in letting kids play. I wanted only one thing, to help those 10-year-olds develop. Like many others, I felt that play was a “healthy part” a sort of play vitamin to high performance, but surely, the mess around, silly stuff could never develop a soccer player, could it?

But we watched the children carefully we saw this was not the case. Free play was the essential ingredient that it allowed kids to acquire skills in ways that far outpaced traditional coaching.

Coaching soccer over so many years, on the ground as kids gain skills, I could divine where those skills emerged. As sure as a F16 pilot can determine that the flying object defying physics is a UFO, I could see where play defies our understanding of skill acquisition.

Seeing how well play delivered skills we went looking for a model. We thought someone must be building play into the curriculum. But we couldn’t find it anywhere, in any sport. While the very best in all sports were emerging from the streets, the academies, schools, and organizations were moving in the other direction, toward more and more structure for youth.

It was as if the experts were flying as kids but when it came to development, everyone preferred to walk, and not only that but with a coach who told them when and how to step and with which foot.

We then understood that if we wanted to deliver the best education possible, we needed to understand exactly what was going on, what play was and how it delivers skill, talent, and expertise, and why everyone was ignoring it.

So as we approached play we understood we would be traveling a path not taken before. This book is about what we discovered: a new way to look at actions, movement, play, talent, and expertise.

Play is much more than “fun and games”. And certainly not “practice lite”. We will show how play works as a communication system, a sort of proto-language, marshaling almost superhuman powers if we can “speak” it fluently. How it delivers easier and smarter as an adaptive countermeasure to bigger, faster, stronger. How it understands talent and expertise more clearly, and how it does all this in the background, quietly to not give itself away. We will show how the greats use it and how we can use play to create better sports, education, and business environments, a hopeful message for kids, adults, and communities.

Ted Kroeten | Joy of the people

This is the opening intro to Ted’s book on play. The book will be published soon. If you don’t want to miss its launch and more related content, follow the links below:

Website of Joy of the People | Twitter of Joy of the People

Fosbury Flop is for the people, by the people. If it brings you value and you want to support the project, you can help to make it possible recommending it to a friend or upgrading your subscription.